ATTENTION ALL CUSTOMERS:

Due to a recent change in our pharmacy software system, all previous login credentials will no longer work.

Please click on “Sign Up Today!” to create a new account, and be sure to download our NEW Mobile app!

Thank you for your patience during this transition.

Get Healthy!

- Posted October 19, 2023

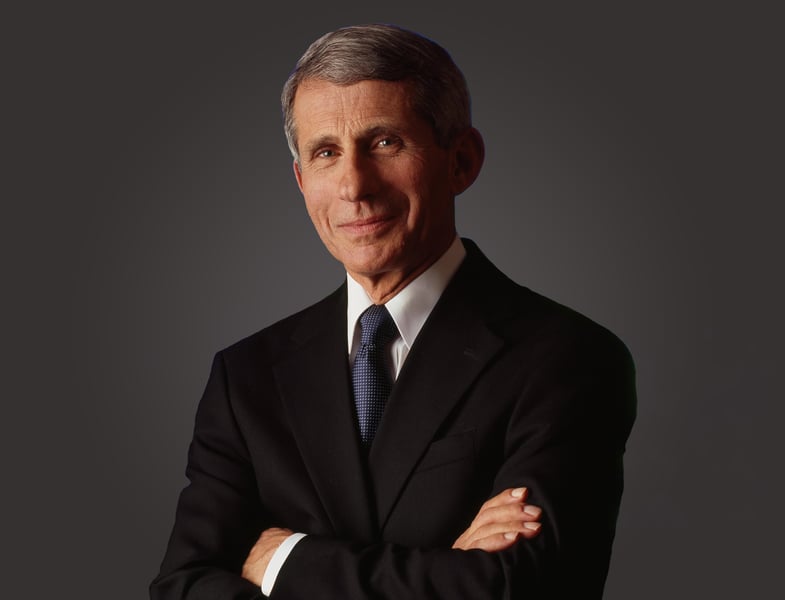

What Keeps Dr. Anthony Fauci Awake at Night

When the pandemic hit, Dr. Anthony Fauci saw his "worst nightmare" realized. Now, a different worry keeps him up at night: that humanity will forget the lessons learned.

That's the crux of a new editorial penned by Fauci, who became a household name in 2020 after quietly leading the U.S. National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for nearly four decades.

Those years saw many challenges, including the HIV/AIDS crisis. Yet the thing that persistently kept him up at night, Fauci says, was the threat of a deadly pandemic caused by a virus that spreads through the air. When that threat turned into a reality in 2020, that was the "nightmare."

Now a professor at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., Fauci no longer has "pandemic response" as a job duty. But he is still thinking about the next pandemic -- which is a matter of "when," not "if."

Writing in the Oct. 18 issue of the journal Science Translational Medicine, Fauci describes some critical lessons from the U.S. pandemic response and puts them into two "buckets."

One is the "scientific bucket," which holds the big success story of the pandemic: the rapid development of vaccines that greatly reduced the risk of severe COVID infection. Over two years, vaccination saved an estimated 3.2 million Americans' lives, according to an analysis by the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund.

Then, Fauci writes, there is the "public health bucket." That one is a mixed bucket, at best.

Vulnerabilities were revealed

The United States struggled at the public health end, with the pandemic amplifying longstanding problems like hospital staff shortages; years of reduced funding for the public health system, which stymied efforts to track COVID cases, do contact tracing and more; and racial disparities in Americans' health care system.

It's well known that Americans of color were especially hard-hit by the pandemic, said Dr. Joseph Betancourt, president of the Commonwealth Fund.

Before taking that job almost a year ago, Betancourt was based at Massachusetts General Brigham, where he helped lead the health system's pandemic response.

He said that one of the biggest lessons from it all is the need to focus on vulnerable communities. That includes the "essential workers" who cannot work from home and often rely on public transportation or live in crowded housing that furthers the spread of respiratory infections.

Rapid, decisive steps have to be taken, Betancourt said, to limit disease spread in communities -- "where the fire is" -- and not only in hospitals and other health care settings.

"Vulnerable people always suffer the most during a natural disaster, including a pandemic," Betancourt said.

If a new pandemic virus emerged this winter, would the United States be better prepared this time?

"To some degree," Betancourt said. "But I'm still concerned."

One key to preparedness, he said, will be global infectious disease surveillance, to spot "what's coming" before being overwhelmed by it.

Another major piece will be communication and coordination among public health departments, which in the United States are scattered at federal, state and local levels. "In Massachusetts, where I worked," Betancourt noted, "every single town had its own public health department."

Then there's the huge challenge of getting clear information to the public in real time, and trying to counter "disinformation."

"All the best science in the world means nothing," Betancourt said, if you fail to communicate it well.

Public health officials, he noted, sent out confusing messages on issues like wearing masks -- which at first was discouraged, then encouraged.

During a pandemic, where scientists and health officials are trying to understand a new virus and track a rapidly evolving situation, the "current" understanding will change over time. And the people communicating that information, Betancourt said, need to be forthright about that.

"I think we need to have a sense of humility, keep things simple and be clear, 'I'm telling you what we know right now,'" Betancourt said.

"Poor public health communication," he added, "creates fertile ground for disinformation. It's fodder for conspiracy theories."

And even people not inclined to buy such theories can get frustrated with confusing messaging. "There can be a feeling of 'We're being told what to do, and they're not even right,'" Betancourt said.

One way to address misinformation, and outright disinformation, is by engaging "trusted messengers," Betancourt said. Those are leaders in local communities who can help spread reliable public health information. It's an on-the-ground countermeasure to the messages that spread like wildfire across social media.

"And that communication system needs to be built now," Betancourt noted.

Politics muddied the message

Fauci, too, pointed to disinformation being "the enemy of the public good," not only in the United States but in many countries. However, he added, the United States had a particularly "profound degree of political divisiveness" that interfered with the public health response to COVID.

Now, Fauci said, the overarching challenge is to clearly see the lessons from COVID and remember them.

"Over and over, after time has passed from the appearance of an acute public health challenge, and after cases, hospitalizations, and deaths fall to an 'acceptable' level "¦ the transition from being reactive to the dwindling challenge to being durably and consistently prepared for the next challenge seems to fall flat," he wrote in his editorial.

"Hopefully, corporate memory of COVID-19 will endure and trigger a sustained interest and support of both the scientific and public health buckets," Fauci wrote. "If not, many of us will be spending a lot of time awake in bed or having nightmares when asleep!"

"There are so many lessons here," Betancourt agreed. "We have to make sure they're sustained. The simplest point here is, do you want to go through that again?"

More information

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has more on pandemic preparedness.

SOURCES: Joseph Betancourt, MD, MPH, president, Commonwealth Fund, New York City; Science Translational Medicine, Oct. 18, 2023, online